https://www.sitepoint.com/how-to-use-ssltls-with-node-js/

It’s time! No more procrastination and poor excuses: Let’s Encrypt works beautifully, and having an SSL-secured site is easier than ever.

In this article, I’ll work through a practical example of how to add a Let’s Encrypt-generated certificate to your Express.js server.

But protecting our sites and apps with HTTPS isn’t enough. We should also demand encrypted connections from the servers we’re talking to. We’ll see that possibilities exist to activate the SSL/TLS layer even if it wouldn’t be enabled by default.

Let’s start with a short review of HTTPS’s current state.

HTTPS Everywhere

The HTTP/2 specification was published as RFC 7540 in May 2015, which means at this point it’s a part of the standard. This was a major milestone. Now we can all upgrade our servers to use HTTP/2. One of the most important aspects is the backwards compatibility with HTTP 1.1 and the negotiation mechanism to choose a different protocol. Although the standard doesn’t specify mandatory encryption, currently no browser supports HTTP/2 unencrypted. This gives HTTPS another boost. Finally we’ll get HTTPS everywhere!

What does our stack actually look like? From the perspective of a website running in the browser (application level) we have roughly the following layers to reach the IP level:

- Client browser

- HTTP

- SSL/TLS

- TCP

- IP

HTTPS is nothing more than the HTTP protocol on top of SSL/TLS. Hence all the rules of HTTP still have to apply. What does this additional layer actually give us? There are multiple advantages: we get authentication by having keys and certificates; a certain kind of privacy and confidentiality is guaranteed, as the connection is encrypted in an asymmetric manner; and data integrity is also preserved: that transmitted data can’t be changed during transit.

One of the most common myths is that using SSL/TLS requires too many resources and slows down the server. This is certainly not true anymore. We also don’t need any specialized hardware with cryptography units. Even for Google, the SSL/TLS layer accounts for less than 1% of the CPU load. Furthermore, the network overhead of HTTPS as compared to HTTP is below 2%. All in all, it wouldn’t make sense to forgo HTTPS for having a little bit of overhead.

The most recent version is TLS 1.3. TLS is the successor of SSL, which is available in its latest release SSL 3.0. The changes from SSL to TLS preclude interoperability. The basic procedure is, however, unchanged. We have three different encrypted channels. The first is a public key infrastructure for certificate chains. The second provides public key cryptography for key exchanges. Finally, the third one is symmetric. Here we have cryptography for data transfers.

TLS 1.3 uses hashing for some important operations. Theoretically, it’s possible to use any hashing algorithm, but it’s highly recommended to use SHA2 or a stronger algorithm. SHA1 has been a standard for a long time but has recently become obsolete.

HTTPS is also gaining more attention for clients. Privacy and security concerns have always been around, but with the growing amount of online accessible data and services, people are getting more and more concerned. A useful browser plugin is “HTTPS Everywhere”, which encrypts our communications with most websites.

The creators realized that many websites offer HTTPS only partially. The plugin allows us to rewrite requests for those sites, which offer only partial HTTPS support. Alternatively, we can also block HTTP altogether (see the screenshot above).

Basic Communication

The certificate’s validation process involves validating the certificate signature and expiration. We also need to verify that it chains to a trusted root. Finally, we need to check to see if it was revoked. There are dedicated trusted authorities in the world that grant certificates. In case one of these were to become compromised, all other certificates from the said authority would get revoked.

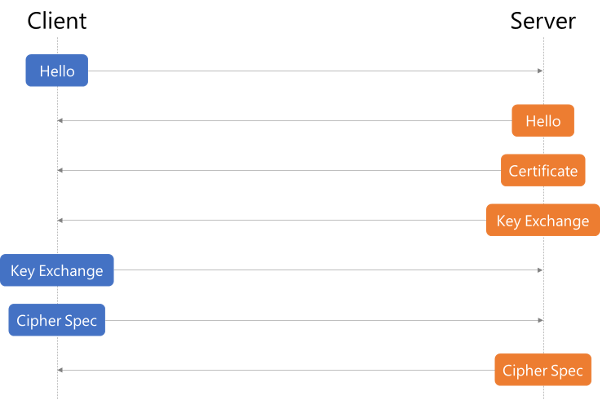

The sequence diagram for a HTTPS handshake looks as follows. We start with the init from the client, which is followed by a message with the certificate and key exchange. After the server sends its completed package, the client can start the key exchange and cipher specification transmission. At this point, the client is finished. Finally the server confirms the cipher specification selection and closes the handshake.

The whole sequence is triggered independently of HTTP. If we decide to use HTTPS, only the socket handling is changed. The client is still issuing HTTP requests, but the socket will perform the previously described handshake and encrypt the content (header and body).

So what do we need to make SSL/TLS work with an Express.js server?

HTTPS

By default, Node.js serves content over HTTP. But there’s also an HTTPS module which we have to use in order to communicate over a secure channel with the client. This is a built-in module, and the usage is very similar to how we use the HTTP module:

const https = require("https"),

fs = require("fs");

const options = {

key: fs.readFileSync("/srv/www/keys/my-site-key.pem"),

cert: fs.readFileSync("/srv/www/keys/chain.pem")

};

const app = express();

app.use((req, res) => {

res.writeHead(200);

res.end("hello world\n");

});

app.listen(8000);

https.createServer(options, app).listen(8080);

Ignore the /srv/www/keys/my-site-key.pem and and /srv/www/keys/chain.pemfiles for now. Those are the SSL certificates we need to generate, which we’ll do a bit later. This is the part that changed with Let’s Encrypt. Previously, we had to generate a private/public key pair, send it to a trusted authority, pay them and probably wait a bit in order to get an SSL certificate. Nowadays, Let’s Encrypt generates and validates your certificates for free and instantly!

Generating Certificates

Certbot

A certificate, which is signed by a trusted certificate authority (CA), is demanded by the TLS specification. The CA ensures that the certificate holder is really who he claims to be. So basically when you see the green lock icon (or any other greenish sign to the left side of the URL in your browser) it means that the server you’re communicating with is really who it claims to be. If you’re on facebook.com and you see a green lock, it’s almost certain you really are communicating with Facebook and no one else can see your communication — or rather, no one else can read it.

It’s worth noting that this certificate doesn’t necessarily have to be verified by an authority such as Let’s Encrypt. There are other paid services as well. You can technically sign it yourself, but then the users visiting your site won’t get an approval from the CA when visiting and all modern browsers will show a big warning flag to the user and ask to be redirected “to safety”.

In the following example, we’ll use the Certbot, which is used to generate and manage certificates with Let’s Encrypt.

On the Certbot site you can find instructions on how to install Certbot on your OS. Here we’ll follow the macOS instructions. In order to install Certbot, run

brew install certbot

Webroot

Webroot is a Certbot plugin that, in addition to the Certbot default functionallity which automatically generates your public/private key pair and generates an SSL certificate for those, also copies the certificates to your webroot folder and also verifies your server by placing some verification codes into a hidden temporary directory named .well-known. In order to skip doing some of these steps manually, we’ll use this plugin. The plugin is installed by default with Certbot. In order to generate and verify our certificates, we’ll run the following:

certbot certonly --webroot -w /var/www/example/ -d www.example.com -d example.com

You may have to run this command as sudo, as it will try to write to /var/log/letsencrypt.

You’ll also be asked for your email address. It’s a good idea to put in a real address you use often, as you’ll get a notification if your certificate expires is about to expire. The trade off for Let’s Encrypt being a free certificate is that it expires every three months. Luckily, renewal is as easy as running one simple command, which we can assign to a cron and then not have to worry about expiration. Additionally, it’s a good security practice to renew SSL certificates, as it gives attackers less time to break the encryption. Sometimes developers even set up this cron to run daily, which is completely fine and even recommended.

Keep in mind that you have to run this command on a server to which the domain specified under the -d (for domain) flag resolves — that is, your production server. Even if you have the DNS resolution in your local hosts file, this won’t work, as the domain will be verified from outside. So if you’re doing this locally, it will most likely not work at all, unless you opened up a port from your local machine to the outside and have it running behind a domain name which resolves to your machine, which is a highly unlikely scenario.

Last but not least, after running this command, the output will contain paths to your private key and certificate files. Copy these values into the previous code snippet, into the cert property for certificate and key property for the key.

// ...

const options = {

key: fs.readFileSync("/var/www/example/sslcert/privkey.pem"),

cert: fs.readFileSync("/var/www/example/sslcert/fullchain.pem") // these paths might differ for you, make sure to copy from the certbot output

};

// ...

Tighetning It Up

HSTS

Have you ever had a website where you switched from HTTP to HTTPS and there were some residual redirects still redirecting to HTTP? HSTS is a web security policy mechanism to mitigate protocol downgrade attacks and cookie hijacking.

HSTS effectively forces the client (browser accessing your server) to direct all traffic through HTTPS – a “secure or not at all” ideology!

Express JS doesn’t allow us to add this header by default, so we’ll use Helmet, a node module that allows us to do this. Install Helmet by running

npm install --save helmet

Then we just have to add it as a middleware to our Express server:

const https = require("https"),

fs = require("fs"),

helmet = require("helmet");

const options = {

key: fs.readFileSync("/srv/www/keys/my-site-key.pem"),

cert: fs.readFileSync("/srv/www/keys/chain.pem")

};

const app = express();

app.use(helmet()); // Add Helmet as a middleware

app.use((req, res) => {

res.writeHead(200);

res.end("hello world\n");

});

app.listen(8000);

https.createServer(options, app).listen(8080);

Diffie–Hellman Strong(er) Parameters

In order to skip some complicated math, let’s cut to the chase. In very simple terms, there are two different keys used for encryption, the certificate we get from the certificate authority and one that’s generated by the server for key exchange. The default key for key exchange (also called Diffie–Hellman key exchange, or DH) uses a “smaller” key than the one for the certificate. In order to remedy this, we’ll generate a strong DH key and feed it to our secure server for use.

In order to generate a longer (2048 bit) key, you’ll need openssl, which you probably have installed by default. In case you’re unsure, run openssl -v. If the command isn’t found, install openssl by running brew install openssl:

openssl dhparam -out /var/www/example/sslcert/dh-strong.pem 2048

Then copy the path to the file to our configuration:

// ...

const options = {

key: fs.readFileSync("/var/www/example/sslcert/privkey.pem"),

cert: fs.readFileSync("/var/www/example/sslcert/fullchain.pem"), // these paths might differ for you, make sure to copy from the certbot output

dhparam: fs.readFileSync("/var/www/example/sslcert/dh-strong.pem")

};

// ...

Conclusion

In 2018 and beyond, there’s no excuse to dismiss HTTPS. The future direction is clearly visible — HTTPS everywhere! In Node.js, we have a lot of options to utilize SSL/TLS. We can publish our websites in HTTPS, we can create requests to encrypted websites and we can authorize otherwise untrusted certificates.

What’s your opinion on HTTPS everywhere? Are there Node.js packages for anything SSL/TLS related that you’d recommend?

For a high-quality, in-depth introduction to Node.js, you can’t go past Learn Node, a course by renowned Canadian full-stack developer Wes Bos. Use the code SITEPOINT to get 25% off!